BW BC 09: Death is Your Friend So Get Comfortable With Them

What Ho, Black Water fans!

We have two stories this week, well actually, we have three stories, but the second one’s not really worth talking about much. So let’s talk about that one first!

Jean Cocteau’s “Death and the Gardener” is a flash length retelling of that story where a guy sees Death, and Death sees him, and the guy leaves town, only for Death to say to some other guy, “Funny seeing that guy here, because I have a meeting with him tonight in [whatever town the guy fled too].” It’s not a bad story, but once you know the twist there’s not much else going on with it. The good bit about this story is in the pre-story blurb where our editor Manguel gives us this quote from Cocteau:

“We need Death to be a friend. It is best to have a friend as traveling companion when you have so far to go together.”

Now to the heftier stories.

In 1975 the Times of London hosted a ghost story contest with Kingsley Amis, Patricia Highsmith (!), and Christopher Lee as the judges(!!). Our story “A Scent of Mimosa” by Francis King won second place. And while it’s a bit conventional in plot, it’s fun in its characterizations as it involves writers, literary prizes, and award ceremonies.

We follow Lenore who’s recently won the Katherine Mansfield prize. She’s in France to receive the prize, traveling with a trio of judges, who are all cringe-worthy literary types. Would you like to hang out with the snob, the surly one, or the one who’s always finding reasons to touch you? Congratulations! You don’t have to choose because you’re stuck in a car with all three! As the ceremonies proceed, Lenore finds her life echoing Mansfield’s (the tuberculosis parts) and finds herself drawn to a strange man she encounters while listening to the speeches. The two connect, and Lenore’s fascinated by him, but somehow he’s never around whenever she wants to find him. Of course, he’s a ghost (Mansfield’s brother who died during World War I), but it’s cool because he says he’ll see her soon and Lenore realizes she’s okay with that. Hence the Cocteau story and quote that follows right after.

Our third story is Somerset Maugham’s “Lord Mountdrago”. It’s about a Doctor Audlin who uses his powers of being very boring to become a therapist. You see he’s so boring he can hypnotize people by the power of his monotone voice alone. One day a new client shows up, our titular Lord Mountdrago, and he’s a conservative politician in parliament and a horrible snob. His trouble is that he keeps having dreams where he keeps running afoul of rival politician, a Welsh Labour MP named Owen Griffith. He fears he will go mad if these dreams aren’t resolved, but when Doctor Audlin suggests a simple cure, Lord Mountdrago refuses to do it, as it requires too great a sacrifice to his pride. And of course that choice ends in disaster.

Like the Francis King story, this one provides some rich characterization. The dreams where Griffith taunts Lord Mountdrago are funny because they’re banal junk described by a person who believes himself superior to such dreams. And the feud between the two men is less ideological than something out of an elementary school classroom. Maugham goes down deep into the particulars to suggest the universal. It’s an enjoyable ride, so vivid in its depiction that even ultra-boring Doctor Audlin gets a rich interior life. Although, by story’s end he’s had a shock that forces him to question everything he thought he knew about the world.

No joke. These are some good stories. And so far this anthology is one that I’m happy to have managed to track down.

Next week… a literal Fash, a little flash, and Jules Verne!

May we all be here to read it.

BWBC 07: The Supernatural Commonplace

Three short, grisly stories from Black Water this week and I’m starting to feel like this anthology is the mix-tape Alberto Manguel made to impress Jorge Borges.

The first story, “An Injustice Revealed” by Anonymous, comes from 6th century China and I feel that Manguel really missed an opportunity to talk about P’u Songling here. For anyone that doesn’t know, P’u Songling was an 18th century collector of strange tales from China and those stories, like this one, have a tone that’s simultaneously desolate churchyard and cosmopolitan city (with a good bit of the bawdy and scatological thrown in). The weirdness comes across in how commonplace the supernatural seems. “An Injustice Revealed” is typical of the style and shifts from the previous stories in the anthology by the fact that the ghost here is treated like any other welcome visitor.

Ye Ning-Fei, a government inspector, has come to the province to uncover the local Governor’s corruption. Ye’s friend, Wang Li, was the previous inspector to the province and died while investigating the same Governor. One night as Ye sits going over the books Wang appears and asks Ye to do him a favor. Basically, a bureaucratic snafu has caused his soul to get separated from his corpse and now he can’t pay the spirit-money necessary to cross from one spirit-province to the other. Would Ye be so good as to burn some spirit money for him so he can pay the tolls? Ye agrees, but wants to hear more about the afterlife. Wang tells him about his trial in the Court of Hell and the mistake that saw his soul locked up there. This mistake points to the Governor’s corruption and from it Ye gets the name of a person wronged by the Governor. But it doesn’t matter much because the Governor dies and goes to Hell, which Wang knew all about because he heard the details of the case while trapped down there.

It’s a good story, but reads more like a treatment than an actual story. Again, if you want to read more stuff like it I recommend you track down a P’u Songling collection. It’s like a collection of News of the Weird that’s a thousand years old.

“A Little Place Off the Edgeware Road” by Graham Greene continues this mix of the supernatural and the commonplace. In a throw back to an earlier story we get treated to another dilapidated movie house and the sad clientele drawn to such places. Only Craven, the story’s main character, is no Pablo Gonzales hoping to find love. Instead, Craven is your typical young male depressive out wandering in the rain beneath the burden of their own intrusive thoughts. To take his mind off his particular fixation, which involves graves and the fact that “under the ground the world was littered with masses of dead flesh ready to rise again”, Craven decides to stop by a rundown theater and watch a movie. Midway through a man sits down beside him, and as murder gets done on screen this man starts whispering to Craven how different actual murder is from the one depicted. At a few points this man even takes Craven’s hand and occasionally coughs on him. All told Craven’s utterly repulsed by the guy. When the movie ends the man leaves as the house lights come up but he doesn’t get away before Craven sees he’s covered in blood. Being a law-abiding sort Craven calls the cops, saying he’s found a wanted murderer. But the cops say it’s not the murderer that’s missing, but the victim’s corpse. At that moment Craven catches sight of himself reflected in the phone booth’s window and his face is covered in blood as if it had been sprayed with a fine mist. With this revelation he promptly has a nervous breakdown. The End.

The MR James piece is from “A School Story” and it’s a snippet of a conversation between two horror story connoisseurs one-upping each other with scary stories. Coming where it does, I can’t help but see it as a critique on Manguel’s project as a whole, warning us that the wondrous can become dull when we indulge in it too often.

Next week, a Signalman and a Tall Woman.

BWBC 06: The Good Bit

Two short ones this week: LP Hartley’s “A Visit from Down Under” and Saki’s “Laura”. They’re good, but also both very much the kind of story you see in anthologies of the Classic British Ghost Story sort.

Hartley is probably most famous as the guy who said a thing, which in this case is the quote “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” See? You have heard of him before! “A Visit From Down Under” starts on a rainy London bus with a strange man all bundled up and sitting on the upper deck in the rain. He’s very peculiar. In particular he is cold to the touch. The ticket collector wants nothing to do with him and only reluctantly goes to tell him when they have reached his stop. Only when he goes to tell the man, the ticket collector discovers that the man has disappeared. FLASHBACK to five hours earlier and a Mr. Rumbold has arrived at his hotel (which is on the street where the strange passenger wanted to stop) after being away so long in Australia. He sets about drinking and making himself comfortable, exchanging some bantering talk with one of the hotel servants about murder. Then he dozes off while listening to a children’s show on the radio. The show takes on ominous overtones becoming increasingly more creepy the longer it goes on, until finally it triggers a panic attack in Rumbold who flees to his room. Later the strange passenger from the opening scene arrives and soon enough Mr. Rumbold is murdered with no trace left but for an icicle melting on the mantle piece.

All told this story exists entirely on the surface with inference made to Rumbold’s crimes. but nothing explicit is revealed. While the end is pretty basic with some wronged ghost coming back to have revenge on the person responsible for their death, the execution is quite good. The bit with the children’s radio show is great, genuinely creepy, as Rumbold can’t keep himself from getting caught up and eventually menaced by its whimsy. Kids’ shows are creepy! Track this story down and read it for that scene alone.

If Hartley’s story was all exteriority without much in the way of introspection, Saki’s “Laura” goes even further. Here the scenes are nearly all dialogue with people saying things that push the story along. We have Laura, a dying woman, Amanda, her friend, and Egbert, Amanda’s husband. Laura jokes about how after her death she’ll return as an otter or some creature, and to be frank she’d looking forward to it, especially if she can be an otter that kills all of Egbert’s chickens. When this comes to pass, Amanda tries to save the otter, but Egbert hunts it down. This results in Amanda having an episode, so Egbert takes her to Egypt to recover, where he is plagued again by another of Laura’s incarnations, and now Amanda is seriously ill. The End.

It’s light all the way through, maybe too much so, as I doubt I’ll remember it a month from now. Yet… well, I have to admire a story that’s all polished surface and light as cotton candy. The skill and craftsmanship on display in such a story are appealing no matter how light they seem. And it’s PG Wodehouse and Oscar Wilde territory, except with higher polish. So don’t be surprised if someday I own one of his story collections.

Next week… Anonymous and Graham Greene!

BWBC 05: A Thousand Words Tell a Picture

Welcome to portrait country.

Not physical portraits as in the Dorian Gray sense (although one does show up in our second story “Enoch Soames”), but the prose sort. First in the short ghost story “Importance” by Manuel Mujica Lainez, about a Mrs. Hermosilla Del Fresno, a self-important woman whose soul after her death lingers on for eternity among her possessions, and second in Max Beerbohm’s longer story about time travel, deals with the devil, and “Enoch Soames”, its titular self-important writer of dubious quality.

I’ve little to say about “Importance”. It’s a good story, concisely told and with a barb to it. Mrs. Hermosilla Del Fresno is a very important widow, nearly the most important widow in her city. The one blemish in her pedigree is that she comes from a less than spectacular family. All of whom she cut out of her life as she rose in society. Then, as these things happen, she woke up one morning only to find herself dead. At first she assumed it was only a matter of time before the angels appeared to take her on to her celestial reward, but as time goes by, and her dreaded relations reappear, she realizes that no angels are coming for her, and this is to be her eternity, her soul trapped in her bedroom, ever aware of how her family degrades her memory.

It’s a good solid shot of smugness followed by impotent rage towards God and man.

What’s not to like?

I hadn’t heard of Lainez until now and it appears his books were never much translated into English. The two that were, Bomarzo about an immortal Renaissance duke and The Wandering Unicorn a tale about the fairy Melusine set against the back drop of the Crusades, sound right up my alley and will likely warrant some tracking down or interlibrary loan next time I’m in the USA.

Now back to the Black Water and “Enoch Soames”…

I don’t know if Max Beerbohm is much remembered these days. He’s certainly someone that shows up a lot in any book about early 20th century English Literature, but more as a scenester than an actual writer. The sort who draws funny pictures of literati and has those pictures and his bon mots published in the smart set papers. Beerbohm’s funny, and perceptive, but a bit arch and smugly long winded in that British high society sort of way. If he were alive today, he’d very likely have a very popular podcast or even late night talk show.

“Enoch Soames” starts as a cutting satire of a certain type of wannabe writer. Soames is the arrogant dabbler who lurks at the margins of the literary scene whose overwhelming sense of self-importance is so distant from his actual ability and output to make him a farcical character. He apes the decadent style while also dismissing it and everything else that crosses his field of vision while working intently on some niche work he proclaims to be nothing shor of groundbreaking. When it’s published it has the title “Fungoids” and no more than three people buy it.

Beerbohm recounts meeting Soames on multiple occasions and finds him morbidly fascinating. As things progress, Soames worries more and more about his legacy and whether people will realize his genius after his death. He’s nearing a fever pitch when the devil steps in (or speaks up since he’s sitting next to Soames and Beerbohm in a crowded café) and offers to transport Soames exactly one hundred years into the future in exchange for his soul. Soames makes the deal and from that point on things go very badly for Enoch Soames.

First he’s not remembered as a significant writer at all. Second, he’s not even real but an imaginary character most famous as the subject of Max Beerbohm’s short story “Enoch Soames”. This leaves him crushed and deflated, so that when he returns to his own present day he’s unable to resist when the devil comes calling for him. The devil here is the theatrical sort dressed in pure Mephistopheles. Beerbohm describes him as looking like the sort of criminal that lingers around train stations in the hopes of stealing some high-class lady’s jewelry case.

As a rather Soamesian sort myself, the story did make me cringe. Beerbohm’s best remembered as a caricaturist after all. The portrait is perfect and Soames has a vividness despite his being described as “dim”. Trust me, if you have ever at all been near any sort of scene then you have met guys like Enoch Soames with their unwarranted high opinions of themselves. That Beerbohm paints his picture and then erases it in the same story is a clever act.

Next week. . . more writers I’ve only heard about but never read!

BWBC 04: Mundane Miracles, Mundane Horrors

In an English cottage two old women sit and drink tea. Outside, the modernizing world makes its noisome rumbles and smoke. Inside, the women eat small sandwiches, sip tea, and gossip about the lives they’ve led. One, the sick one, begins to tell a story. It is not a love story but it is a story about love and devotion and a deserted house where something called a “token” lives. If you go to the house and stand outside the door the token will listen and let you take on someone else’s troubles for your own. The woman went there for love, so she might take on all the pain destined to come to her man. It didn’t matter that she could never be with that man. She was his and that was all that mattered. Now, the cancer on her leg grows, and the story ends when the nurse arrives and complains about old ladies and their gossip.

That’s the outline of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Wish House”. A story I like more as an idea than in its written form. It’s all told in a very roundabout way, and by the time the actual Wish House appears it’s easy to have gotten distracted by the why’s why and who’s who in the story. But retelling the story above, the idea becomes visible again and I’m once more interested in the “token”.

Other sites will go into the Christian symbolism Kipling employs in the story. The sick woman’s name is Grace. GRACE! Get it? But all that’s pretty scant sauce on an idea I wish had more exploration.

Now on to a story about a suburban father who fears for his son and what he’ll learn about life down at “The Playground.” This is a Ray Bradbury story, so it’s ripe with what now reads as corny Twilight Zone weirdness, but that’s only because Ray Bradbury was as good as he was and made his legacy ubiquitous.

This is an anti-nostalgia story with an adult remembering their childhood as an era of brutality and powerlessness. The father views the playground in question as a demonic place where children are introduced to the world’s cruelties and it’s now his responsibility to protect his child from those same cruelties. That the playground has the supernatural power to spare the son by sacrificing the father (Get it!?!) pushes this into the fantastic.

“The Playground” has some great descriptive passages in it as Bradbury renders hop-scotch outlines, slides, and swing-sets through a lens that would do Hieronymus Bosch proud. Also when set right after the Kipling story the whole notion of taking on another’s troubles as one’s own becomes much more sinister. Kipling’s a believer in his story, while Bradbury is an agnostic at best. Sure, the playground has a manager and the light is on all the time in their office, but no one’s ever in there and the manager’s never been seen.

I feel like I should read more Ray Bradbury. At the same time I feel like I’ve already read too much Ray Bradbury. Yet, I haven’t really read all that much Ray Bradbury. It’s just that decades of entertainment have absorbed so much Ray Bradbury that we’ve all read Ray Bradbury without having read Ray Bradbury at all.

Next week some more spooky shit!

BWBC 03: Jealous Again

Today on Black Water Book Club dead lovers once more appear and jealousy rears its ugly head.

First, Edith Wharton’s “Pomegranate Seed” about Charlotte, a newly married woman trying to uncover the truth about the mysterious letters her husband keeps receiving. That the husband’s first wife died tragically lets you know right away where this story is going, and while it delivers few surprises it is a deep dive into an individual’s emotional landscape as they oscillate between jealousy, curiosity, and fear. Wharton’s one of those writers that can have a character walk up the steps to their house then go on for three paragraphs of internal monologue as the character pauses before their door with key in hand. That Charlotte becomes obsessed with finding out the identity of the letter writer leads her to lay a trap for her husband that ultimately has tragic results. Overall, the story’s a bit disappointing. The touch is very light and the haunting raises more questions than it answers. But if you like introspective stories that focus on a character’s emotional landscape, this might be something you enjoy.

Also, a last note about Wharton: I had always associated her with the late 19th century, but she died in the 1930s and was publishing right up until the end of her life. All that’s to say that when the narrator talks about automobiles I did a bit of a double take.

Next we have “Venetian Masks” by Adolfo Bioy Casares, another story about being haunted by the specters of obsession and jealousy, only this time the explanation is scientific as opposed to supernatural. An unnamed narrator describes his love affair to Daniela, a brilliant biologist. As time goes by the affair grows increasingly strained until it ultimately ends, and the narrator tries to move on with his life but fails. Years later he learns his friend married Daniela, and by chance the three encounter each other in Venice during Carnival. Only now it appears that there are at least two Danielas, because of cloning technology and the fact that Daniela’s a brilliant biologist. What she’s done is custom designed cloned versions of herself to give to her former lovers. That’s the reveal, and the narrator’s reaction to this information slams the story shut.

This is the kind of SF story you either love or hate. It’s more interested in the scientific idea of cloning than in how that science would work. And the story plays out in a strange setting that’s ambiguous and confused. It’s Carnival! Everyone’s wearing masks of archetypal characters. Is the narrator only playing a part in some timeless farcical love story? Is Daniela the model for a new Columbina? What sort of future will her technology usher in? How creepy is it that she sells off her clones to her former lovers when she has outgrown those lovers? Who cares! The narrator’s an obsessive hypochondriac prone to psychosomatic illnesses and that condition matters more to the story than any exploration of technology or future world distorted by cloning technology. I am absolutely fine with that and so far alongside “The Mysteries of the Joy Rio” this has been one of my favorite stories in the anthology so far.

Next week, Kipling and Bradbury!

BWBC 02: Climax Joy!

Welcome back to the Black Water Book Club. Today we’ll enjoy a very short one and a somewhat longer one.

IA Ireland’s “Climax For a Ghost Story” is an example of what would today be called flash fiction. It’s very much the kind of story places like Daily Science Fiction publishes regularly. That’s not a quality critique on flash fiction (I quite enjoy writing it myself!), Daily Science Fiction (who do what they do very well), or the story itself, just that its brevity no longer makes an intriguing curiosity but places it in a stylistic tradition. Read it for yourself:

“How eerie!” said the girl, advancing cautiously. “—And what a heavy door!” She touched it as she spoke, and it suddenly swung to with a click.

“Good Lord!” said the man. “I don’t think there’s a handle inside. Why, you’ve locked us both in.”

“Not both of us. Only one of us,” said the girl, and before his eyes she passed straight through the door, and vanished.

… spooky…

What actually makes this story notable is not the story itself but the likelihood that its author never existed and the whole thing’s a fabrication. The story’s said to come from Ireland’s 1919 book Visitations, which there seems to be no record of. Nor is there any record of the existence of Ireland’s 1899 book A Brief History of Nightmares. What is mentioned is that Ireland claims descent from William Henry Ireland, an infamous eighteenth-century forger who tried to pass his plays off as lost works by William Shakespeare. So for now, I’ll believe I.A. Ireland’s a hoax until some librarian tells me otherwise.

Here’s a little bit more on “Climax For a Ghost Story” and the mystery surrounding its author.

On to the next story, a tale of remembrance and loss. . . and getting a hand-job from your dead lover’s ghost until you die. The story’s called “The Mysteries of the Joy Rio”, and it’s written by Tennessee Williams. And here we are going straight into Ick Country of the sort you’ll find in Samuel R. Delany’s writings on New York City’s Times Square.

But first, up front, I’ll just admit that I really, really liked this story. It’s all atmosphere. Yes, squalid, dilapidated, and sordid atmosphere, but that’s a feature not a bug. It’s also kind of a tender love story.

Pablo Gonzales is an aging watch repairman in Texas who is so much surrounded by time as to have become indifferent to its passage, and one day he decides to go to the movies. That’s the story, except more so.

Mr. Gonzales inherited his watch repair business from his long dead lover, Emiel Kroger. That this story is set in 1950s USA means their relationship does not at all look healthy. Kroger’s described as a grotesque (“very fat, very strange”) who picks up a teen-age (possibly underage) Gonzalez for sex one night. That Gonzalez returns Kroger’s affection, surprises the older man, and the two form a relationship that’s both master and apprentice and romantic partner. In time Kroger dies leaving everything he owns to Gonzalez. Meanwhile the local movie palace the Joy Rio descends into decrepitude, becoming the center of an illicit world of sexual practices on its upper floors. Mr. Gonzales is a regular visitor to the upper floors. That this is 1950s USA means all these assignations have to be done subtly or one risks bringing the wrath of society at large down on oneself, no matter how ugly and sordid that greater society might be. There’s a nice anxious paranoia in this story as Mr. Gonzalez navigates the risks and rules of the sorts of seductions carried on in the Joy Rio. When a misstep throws his life in sudden danger, it’s too the upper floors Mr. Gonzalez flees and where the ghost of Emiel Kroger waits.

There’s a companion piece to this story called “Hard Candy” that I hope to read some day, and the Ick Factor here is definitely drawn from Williams’s own life. There’s tenderness within the grotesque on display, and both serve to make this a very unsettling story, perfect for the sort of book the Black Water Anthology hoped to be.

Next week … faint hand-writing and Venetian masks!

BWBC 01: Enter… the Ambiguity

Welcome back to the Back Water Book Club or the BWBC as I’m going to call it from now on. This week we hit the stories!

To start off is Julio Cortazar’s “House Taken Over”.

It’s a ghost story. Sort of.

It’s more a metaphor story, but for what I don’t know. This story has ambiguity dripping all over it. A middle-aged brother and sister living in an old house find themselves at odds with a nameless unseen “they” that shows up one they and starts taking over their home. At first it’s only part of the house, and the brother and sister flee behind a sturdy oak door into another part of the house, but before long the unseen “they” take over even this part, and the brother and sister are forced to flee the house entirely.

But who are “they”? It’s uncertain. They simply appear and instead of confronting them, the brother and sister let them take over the house. Is it scary? Are the brother and sister actually ghosts haunting their ancestral home? Is the haunting actually an indictment of the brother and sister, as the intruders appear to have much more life than either of the pair? The story offers no answers. My reading’s that the “they” are metaphorical, a symbol of the unseen majority that will push the marginalized into the streets unless confronted.

Scary? No. Strange? Kinda. Ambiguous? Oh yeah.

Following that, we have a more traditional story in Robert S. Hichens’s “How Love Came to Professor Guildea”. This one features the recognizable Victorian trope of two old educated bachelors of opposing personalties who manage to be great friends despite their differences. Instead of Holmes and Watson, it’s a Father Murchison and a Professor Guildea. Murchison’s the sentimental idealist, while Guildea’s the man of pure intellect and reason. The two meet and get into debates about the human condition. Then Professor Guildea finds himself haunted.

And it’s here where we encounter the “ick factor” I talked about back in the introduction, because whatever the entity is that attaches itself to the Professor, its main characteristic is that it’s mentally disabled and the chill of the story comes from that fact. The entity that haunts the Professor is described as an imbecile (and not so flattering as such), and this makes both men shudder. While the entity seems to mean no harm, the very affection that it shows the Professor is deemed unnatural and a thing to be feared. And so the men set out to rid themselves of the thing with mixed results.

So, is this scary? Sort of. From the entity’s initial appearance as a ragged form on a park bench to the Professor’s slow discovery of its nature, and the dawning realization of what it wants, the story manages to get under one’s skin and linger. But that it relies on ableism to do so can’t be denied.

Next week… a possible hoax and some more ick factor from Tennessee Williams!

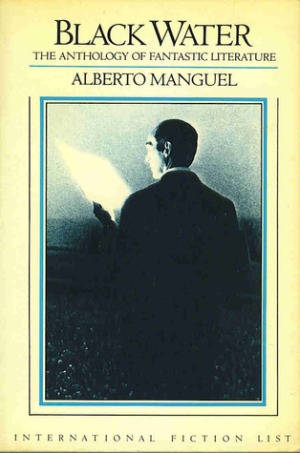

Black Water Book Club

Hello, folks. Welcome to the Black Water Book Club.

Today we’re taking a quick look at the book’s forward before next week when we’ll start looking at the stories proper. Fortunately, the forward’s brief and it gets to the point quickly. Manguel gives a good working definition of what he thinks fantastic literature is:

“Unlike tales of fantasy (those chronicles of mundane life in mythical surroundings such as Narnia or Middle Earth) fantastic literature can best be defined as the impossible seeping into the possible, what Wallace Stevens calls “black water breaking into reality”. Fantastic literature never really explains everything.”

He then outlines the main themes common to all the stories selected for the anthology:

– Time warps

– Hauntings

– Dreams

– Unreal creatures, transformations

– Mimesis (seemingly unrelated acts which secretly dramatize each other)

– Dealings with God and the Devil

“The truly good fantastic story will echo that which escapes explanation in life; it will prove _in fact_ that life is fantastic. It will point to that which lies beyond our dreams and fears and delights; it will deal with the invisible, with the unspoken, it will not shirk from the uncanny, the absurd, the impossible; in short, it has the courage of total freedom.”

One thing I’ll note is that while no story has been steeped in the complete bigotry of, say, an HP Lovecraft story, a few so far have relied on certain prejudices to achieve their impact. That this would be the case in stories that rely on dreams, fears, the absurd, and the uncanny should surprise no one. But this “ick factor” when it occurs can leave a bad taste behind it. The fantastic as Manguel approaches it is not to be mistaken for a clean place at all.

If you want to read more about Alberto Manguel, here’s the link to his wikipedia page. His Dictionary of Imaginary Places is a fun book to spend a few hours with.