BWBC 04: Mundane Miracles, Mundane Horrors

In an English cottage two old women sit and drink tea. Outside, the modernizing world makes its noisome rumbles and smoke. Inside, the women eat small sandwiches, sip tea, and gossip about the lives they’ve led. One, the sick one, begins to tell a story. It is not a love story but it is a story about love and devotion and a deserted house where something called a “token” lives. If you go to the house and stand outside the door the token will listen and let you take on someone else’s troubles for your own. The woman went there for love, so she might take on all the pain destined to come to her man. It didn’t matter that she could never be with that man. She was his and that was all that mattered. Now, the cancer on her leg grows, and the story ends when the nurse arrives and complains about old ladies and their gossip.

That’s the outline of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Wish House”. A story I like more as an idea than in its written form. It’s all told in a very roundabout way, and by the time the actual Wish House appears it’s easy to have gotten distracted by the why’s why and who’s who in the story. But retelling the story above, the idea becomes visible again and I’m once more interested in the “token”.

Other sites will go into the Christian symbolism Kipling employs in the story. The sick woman’s name is Grace. GRACE! Get it? But all that’s pretty scant sauce on an idea I wish had more exploration.

Now on to a story about a suburban father who fears for his son and what he’ll learn about life down at “The Playground.” This is a Ray Bradbury story, so it’s ripe with what now reads as corny Twilight Zone weirdness, but that’s only because Ray Bradbury was as good as he was and made his legacy ubiquitous.

This is an anti-nostalgia story with an adult remembering their childhood as an era of brutality and powerlessness. The father views the playground in question as a demonic place where children are introduced to the world’s cruelties and it’s now his responsibility to protect his child from those same cruelties. That the playground has the supernatural power to spare the son by sacrificing the father (Get it!?!) pushes this into the fantastic.

“The Playground” has some great descriptive passages in it as Bradbury renders hop-scotch outlines, slides, and swing-sets through a lens that would do Hieronymus Bosch proud. Also when set right after the Kipling story the whole notion of taking on another’s troubles as one’s own becomes much more sinister. Kipling’s a believer in his story, while Bradbury is an agnostic at best. Sure, the playground has a manager and the light is on all the time in their office, but no one’s ever in there and the manager’s never been seen.

I feel like I should read more Ray Bradbury. At the same time I feel like I’ve already read too much Ray Bradbury. Yet, I haven’t really read all that much Ray Bradbury. It’s just that decades of entertainment have absorbed so much Ray Bradbury that we’ve all read Ray Bradbury without having read Ray Bradbury at all.

Next week some more spooky shit!

BWBC 03: Jealous Again

Today on Black Water Book Club dead lovers once more appear and jealousy rears its ugly head.

First, Edith Wharton’s “Pomegranate Seed” about Charlotte, a newly married woman trying to uncover the truth about the mysterious letters her husband keeps receiving. That the husband’s first wife died tragically lets you know right away where this story is going, and while it delivers few surprises it is a deep dive into an individual’s emotional landscape as they oscillate between jealousy, curiosity, and fear. Wharton’s one of those writers that can have a character walk up the steps to their house then go on for three paragraphs of internal monologue as the character pauses before their door with key in hand. That Charlotte becomes obsessed with finding out the identity of the letter writer leads her to lay a trap for her husband that ultimately has tragic results. Overall, the story’s a bit disappointing. The touch is very light and the haunting raises more questions than it answers. But if you like introspective stories that focus on a character’s emotional landscape, this might be something you enjoy.

Also, a last note about Wharton: I had always associated her with the late 19th century, but she died in the 1930s and was publishing right up until the end of her life. All that’s to say that when the narrator talks about automobiles I did a bit of a double take.

Next we have “Venetian Masks” by Adolfo Bioy Casares, another story about being haunted by the specters of obsession and jealousy, only this time the explanation is scientific as opposed to supernatural. An unnamed narrator describes his love affair to Daniela, a brilliant biologist. As time goes by the affair grows increasingly strained until it ultimately ends, and the narrator tries to move on with his life but fails. Years later he learns his friend married Daniela, and by chance the three encounter each other in Venice during Carnival. Only now it appears that there are at least two Danielas, because of cloning technology and the fact that Daniela’s a brilliant biologist. What she’s done is custom designed cloned versions of herself to give to her former lovers. That’s the reveal, and the narrator’s reaction to this information slams the story shut.

This is the kind of SF story you either love or hate. It’s more interested in the scientific idea of cloning than in how that science would work. And the story plays out in a strange setting that’s ambiguous and confused. It’s Carnival! Everyone’s wearing masks of archetypal characters. Is the narrator only playing a part in some timeless farcical love story? Is Daniela the model for a new Columbina? What sort of future will her technology usher in? How creepy is it that she sells off her clones to her former lovers when she has outgrown those lovers? Who cares! The narrator’s an obsessive hypochondriac prone to psychosomatic illnesses and that condition matters more to the story than any exploration of technology or future world distorted by cloning technology. I am absolutely fine with that and so far alongside “The Mysteries of the Joy Rio” this has been one of my favorite stories in the anthology so far.

Next week, Kipling and Bradbury!

BWBC 02: Climax Joy!

Welcome back to the Black Water Book Club. Today we’ll enjoy a very short one and a somewhat longer one.

IA Ireland’s “Climax For a Ghost Story” is an example of what would today be called flash fiction. It’s very much the kind of story places like Daily Science Fiction publishes regularly. That’s not a quality critique on flash fiction (I quite enjoy writing it myself!), Daily Science Fiction (who do what they do very well), or the story itself, just that its brevity no longer makes an intriguing curiosity but places it in a stylistic tradition. Read it for yourself:

“How eerie!” said the girl, advancing cautiously. “—And what a heavy door!” She touched it as she spoke, and it suddenly swung to with a click.

“Good Lord!” said the man. “I don’t think there’s a handle inside. Why, you’ve locked us both in.”

“Not both of us. Only one of us,” said the girl, and before his eyes she passed straight through the door, and vanished.

… spooky…

What actually makes this story notable is not the story itself but the likelihood that its author never existed and the whole thing’s a fabrication. The story’s said to come from Ireland’s 1919 book Visitations, which there seems to be no record of. Nor is there any record of the existence of Ireland’s 1899 book A Brief History of Nightmares. What is mentioned is that Ireland claims descent from William Henry Ireland, an infamous eighteenth-century forger who tried to pass his plays off as lost works by William Shakespeare. So for now, I’ll believe I.A. Ireland’s a hoax until some librarian tells me otherwise.

Here’s a little bit more on “Climax For a Ghost Story” and the mystery surrounding its author.

On to the next story, a tale of remembrance and loss. . . and getting a hand-job from your dead lover’s ghost until you die. The story’s called “The Mysteries of the Joy Rio”, and it’s written by Tennessee Williams. And here we are going straight into Ick Country of the sort you’ll find in Samuel R. Delany’s writings on New York City’s Times Square.

But first, up front, I’ll just admit that I really, really liked this story. It’s all atmosphere. Yes, squalid, dilapidated, and sordid atmosphere, but that’s a feature not a bug. It’s also kind of a tender love story.

Pablo Gonzales is an aging watch repairman in Texas who is so much surrounded by time as to have become indifferent to its passage, and one day he decides to go to the movies. That’s the story, except more so.

Mr. Gonzales inherited his watch repair business from his long dead lover, Emiel Kroger. That this story is set in 1950s USA means their relationship does not at all look healthy. Kroger’s described as a grotesque (“very fat, very strange”) who picks up a teen-age (possibly underage) Gonzalez for sex one night. That Gonzalez returns Kroger’s affection, surprises the older man, and the two form a relationship that’s both master and apprentice and romantic partner. In time Kroger dies leaving everything he owns to Gonzalez. Meanwhile the local movie palace the Joy Rio descends into decrepitude, becoming the center of an illicit world of sexual practices on its upper floors. Mr. Gonzales is a regular visitor to the upper floors. That this is 1950s USA means all these assignations have to be done subtly or one risks bringing the wrath of society at large down on oneself, no matter how ugly and sordid that greater society might be. There’s a nice anxious paranoia in this story as Mr. Gonzalez navigates the risks and rules of the sorts of seductions carried on in the Joy Rio. When a misstep throws his life in sudden danger, it’s too the upper floors Mr. Gonzalez flees and where the ghost of Emiel Kroger waits.

There’s a companion piece to this story called “Hard Candy” that I hope to read some day, and the Ick Factor here is definitely drawn from Williams’s own life. There’s tenderness within the grotesque on display, and both serve to make this a very unsettling story, perfect for the sort of book the Black Water Anthology hoped to be.

Next week … faint hand-writing and Venetian masks!

Oh Shit! You’re Trapped in an Irish Fairy Tale

Your step-mom will try to kill you, but she will fail. So instead she’ll turn you and your brothers into swans. After a few centuries you’ll become human again, except you’ll be incredibly old. But fear not! It’ll all be okay because you’ll be baptized before you die.

The king will send you and your brothers on a suicidal mission (because you killed his da), but when you do well the king will have his druid cast a spell so you all forget what it is you’re supposed to be doing. Then three shouts from a hilltop will kill you.

The “Salmon Leap” is the cobra-claw secret move of all Irish heroes, well, that and a short spear stab to the belly.

You’ll know such a terrible secret about the king that you’ll start to die. A druid will tell you to go to the woods and tell the secret to a hole in a tree, but later a fucking bard will show up and make a harp from that very tree that tells everyone the king’s terrible secret. (The king’s secret is that he has horse ears.)

You will go hunting deer, but the deer will tell you to cut that shit out because they’re actually your half-sibling from the gap year your dad/mom spent as a deer because they annoyed a druid. This will also apply to wolfhounds and birds.

The fairies will be small, unless they are big. Either way, you’re likely in for a bad time.

Your dinner will get cold because all the heroes have gotten into a pissing match over who’s most worthy to cut the meat. Eventually this will be settled by a gigantic brawl, which was the whole point of the feast anyway.

Brain-balls are the deadliest missile weapon and made from the brains of a mighty warrior you killed mixed with lime and sculpted into a sling bullet.

The king will get hit in the head with a brain-ball, not die, but live in an infirm state with the ball still in his head. He’ll then die when the druids tell him about Jesus’s death and he gets so angry the brain-ball falls out, killing him.

If you’re a woman your eyes will be hyacinth blue, lips scarlet as rowan berries, feet slim, and the light of the moon will glow from your face.

Don’t drink from that cup! It has elf genetic material in it!

Oh shit, you drank from the cup, now your daughter’s an elf and kings will fight over her, and she will probably get turned into a bird or leaf or breeze, and she’ll spend countless days like this until she meets a monk or elf or druid.

If an elf loans you a horse and tells you not to get off a horse, DON’T GET OFF THE HORSE.

Actually, it’s best to avoid horses all together.

You will be rash and ignorant but eating more fish will make you wise.

Swamps are the best place to practice poetry.

Three things make a poet: the Fire of Song, the Light of Knowledge, and the Art of Improv, or Extempore Recitation as the druids call it.

No brave deed will be done that Conan the Bald won’t mock and belittle.

You will know a guy named Dermot of the Love Spot. You will regret this, but your wife won’t.

Refer to your OCD as a geis and everyone will be cool with it.

Strangely beautiful princesses are either elves… or Greeks… or Picts.

The fairies will steal your stuff and/or family just so you’ll stop by for dinner.

The King will disappear for six months to a year. No one will know where he went and they’ll be much speculation. Say hello to all your new wolf, bird, and deer siblings!

All these come from “The High Deeds of Finn and Other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland” by TW Rolleston. You can download it from Project Gutenberg: gutenberg.org/ebooks/14749

BWBC 01: Enter… the Ambiguity

Welcome back to the Back Water Book Club or the BWBC as I’m going to call it from now on. This week we hit the stories!

To start off is Julio Cortazar’s “House Taken Over”.

It’s a ghost story. Sort of.

It’s more a metaphor story, but for what I don’t know. This story has ambiguity dripping all over it. A middle-aged brother and sister living in an old house find themselves at odds with a nameless unseen “they” that shows up one they and starts taking over their home. At first it’s only part of the house, and the brother and sister flee behind a sturdy oak door into another part of the house, but before long the unseen “they” take over even this part, and the brother and sister are forced to flee the house entirely.

But who are “they”? It’s uncertain. They simply appear and instead of confronting them, the brother and sister let them take over the house. Is it scary? Are the brother and sister actually ghosts haunting their ancestral home? Is the haunting actually an indictment of the brother and sister, as the intruders appear to have much more life than either of the pair? The story offers no answers. My reading’s that the “they” are metaphorical, a symbol of the unseen majority that will push the marginalized into the streets unless confronted.

Scary? No. Strange? Kinda. Ambiguous? Oh yeah.

Following that, we have a more traditional story in Robert S. Hichens’s “How Love Came to Professor Guildea”. This one features the recognizable Victorian trope of two old educated bachelors of opposing personalties who manage to be great friends despite their differences. Instead of Holmes and Watson, it’s a Father Murchison and a Professor Guildea. Murchison’s the sentimental idealist, while Guildea’s the man of pure intellect and reason. The two meet and get into debates about the human condition. Then Professor Guildea finds himself haunted.

And it’s here where we encounter the “ick factor” I talked about back in the introduction, because whatever the entity is that attaches itself to the Professor, its main characteristic is that it’s mentally disabled and the chill of the story comes from that fact. The entity that haunts the Professor is described as an imbecile (and not so flattering as such), and this makes both men shudder. While the entity seems to mean no harm, the very affection that it shows the Professor is deemed unnatural and a thing to be feared. And so the men set out to rid themselves of the thing with mixed results.

So, is this scary? Sort of. From the entity’s initial appearance as a ragged form on a park bench to the Professor’s slow discovery of its nature, and the dawning realization of what it wants, the story manages to get under one’s skin and linger. But that it relies on ableism to do so can’t be denied.

Next week… a possible hoax and some more ick factor from Tennessee Williams!

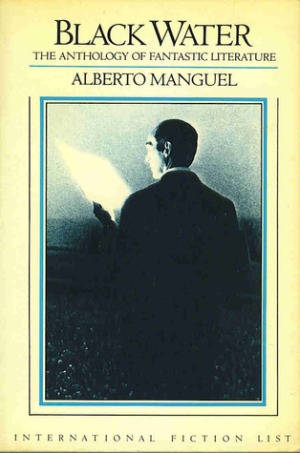

Black Water Book Club

Hello, folks. Welcome to the Black Water Book Club.

Today we’re taking a quick look at the book’s forward before next week when we’ll start looking at the stories proper. Fortunately, the forward’s brief and it gets to the point quickly. Manguel gives a good working definition of what he thinks fantastic literature is:

“Unlike tales of fantasy (those chronicles of mundane life in mythical surroundings such as Narnia or Middle Earth) fantastic literature can best be defined as the impossible seeping into the possible, what Wallace Stevens calls “black water breaking into reality”. Fantastic literature never really explains everything.”

He then outlines the main themes common to all the stories selected for the anthology:

– Time warps

– Hauntings

– Dreams

– Unreal creatures, transformations

– Mimesis (seemingly unrelated acts which secretly dramatize each other)

– Dealings with God and the Devil

“The truly good fantastic story will echo that which escapes explanation in life; it will prove _in fact_ that life is fantastic. It will point to that which lies beyond our dreams and fears and delights; it will deal with the invisible, with the unspoken, it will not shirk from the uncanny, the absurd, the impossible; in short, it has the courage of total freedom.”

One thing I’ll note is that while no story has been steeped in the complete bigotry of, say, an HP Lovecraft story, a few so far have relied on certain prejudices to achieve their impact. That this would be the case in stories that rely on dreams, fears, the absurd, and the uncanny should surprise no one. But this “ick factor” when it occurs can leave a bad taste behind it. The fantastic as Manguel approaches it is not to be mistaken for a clean place at all.

If you want to read more about Alberto Manguel, here’s the link to his wikipedia page. His Dictionary of Imaginary Places is a fun book to spend a few hours with.