Memoirs of Lady Hyegyong

Lady Hyegyong was an 18th century Crown Princess in Korea’s Cho’son dynasty. Her husband was the “infamous” Prince Sado.

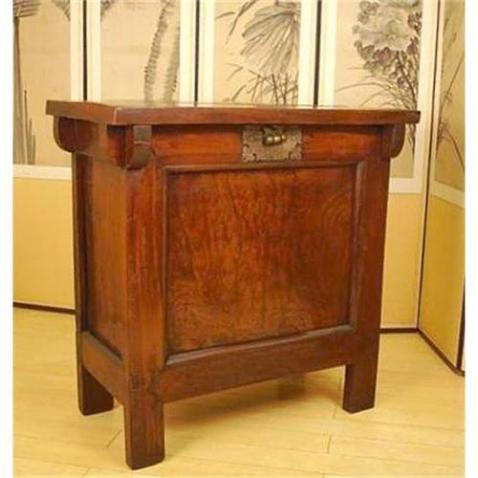

What’s known about Prince Sado is that he was put to death by his parents the King and Queen. Since no one could harm a royal person, Sado was ordered to climb into a rice chest, where he was locked until he suffocated after eight days. The reason given was because Sado was “mad” and considered a risk to the dynasty. In the 19th century there were rumors Sado was not “mad” but the victim of a conspiracy, and his father unjustly killed him. Lady Hyegyong, by now an old woman, decided to counter these rumors and set the record straight. That the late King, Sado’s father, had all mention of the incident removed from castle records, makes Lady Hyegyong’s account the definitive one. And like I said it’s a fascinating book. Lady Hyegyong gives a first hand account of what happened and details Sado’s “madness”.

But that’s not all that’s in this book. There are four memoirs here. In all of them Lady Hyegyong shows herself to be a perceptive judge of character and court life.

The first details Lady Hyegyong’s life from her childhood through her marriage at age nine to Prince Sado, her removal from her family home and her residency in the Royal Palace. From there she speaks briefly of Sado’s tragic life, the aftermath of his death, and her ultimate resolve to keep living and raise their son (who also happened to be the heir to the throne).

The second and third memoirs deal with her family members and their involvement in court intrigues. I recommend skipping these two, and going straight to the last.

The last memoir is a character study of Prince Sado, his illness, and his relationship with his father. It’s highly detailed as if Lady Hyegyong is trying to find the source and cause of Sado’s madness. Was it because he was separated from his parents at an early age, that his father failed to provide him with decent overseers, or something more sinister – such as the proximity of his palace to the ruined palace once belonging to a Queen who poisoned her competitors in the court? What is certain is that Sado’s episodes were often violent and he killed and/or raped many servants. The first Lady Hyegyong witnessed was the death of a eunuch and she speaks of his being the first severed head she had ever seen. Later Sado beat one of his consorts to death, and nearly knocked out one of Lady Hyegyong’s eyes after hitting her in the head with a chess board. These and other instances were what caused the royal family to fear Sado and led them to giving the order that he should be sealed in the rice chest.

As a modern reader it’s impossible not to try and diagnose Sado’s “madness”. That he was neurologically atypical is likely. Possibly he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia or a bipolar disorder. He also exhibited several phobias and obsessive compulsive disorders (Lady Hyegyong talks about a clothing phobia that would require a steady stream of fresh cloth, since Sado would destroy any clothes he found fault with), along with a murderous rage. Yet, Lady Hyegyeong is clear in stating that these were episodic and when he wasn’t in one of these phases Prince Sado could be a kind and gentle man, and often Sado comes across not as a monster but a victim. He suffers, even if he is a murderer.

Then there’s the weird stuff – the things that would make a good horror story. It’s like there’s a ghost story waiting right behind the actual tragedy.

Prince Sado was obsessed with Taoist magic, in particular one book of rites known as the Jade Spine Scriptures. He believed the God of Thunder was angry with him and was terrified by thunder storms (that one occurred on the 8th day after he was locked in the chest doesn’t go unnoticed by Lady Hyegyong). Often he would leave the palace dressed as a commoner and no one knew what he did during these times. And when he died, his father had his associates, a group including several shamans and a Buddhist nun, put to death.

It’s one thing to read about Caligula or some other ancient ruler known for being “mad”. It’s another to have a near modern account of a neurologically atypical ruler, one where the individual is painted so vividly that it’s like looking at an evolving portrait of their life. Lady Hyegyong provides that level of detail in her account, and as a book The Memoirs make for compelling reading. Maybe your library has a copy.

11 responses to “Memoirs of Lady Hyegyong”

Trackbacks / Pingbacks

- - March 30, 2014

- - March 6, 2016

Justin posted: “This is a fascinating book. Lady Hyegyong was an 18th century Crown Princess in Korea’s Cho’son dynasty. Her husband was the “infamous” Prince Sado. What’s known about Prince Sado is that he was put to death by his parents the King and Queen. Since ” An amazing story. Sometimes as in the Duc St. Simonıs memories of Louis XIV and Versailles itıs the incidental details, ³that lady poisoner, childhood companion to the King² that make it all worthwhile. Rick

Just catching up, finally. Yeah, fascinating book, glad you enjoyed it. You definitely mentioned a lot of the stuff that attracted me to the story, and to be frank, I’m shocked it hasn’t been turned into a Korean horror film yet.

I don’t know if you heard about it, but there was a piece in the Korean news, I think about 2007 or so, about some letters being discovered, written by the Crown Prince to his uncle. He apparently was very much aware of something being severely wrong with him, spoke of being unable to control his mind or his behaviour; he also begged his uncle to spend whatever it would cost to get some specific, obscure, and hard-to-get “medicines” (we’re talking traditional Sino-Korean medicine here) to treat his “sickness.” Obviously that didn’t work, but it adds to the horror and the tragedy.

I still have my pseudo-Lovecraftianized Crown Prince Sado novella sitting and waiting, with no idea where to send such a piece. Looking back, I see that I started work on it in 2007! (Yikes!)

That’s the sad part in his story: he very clearly knows something is wrong with himself and is a victim as well as a monster. Lady Hyegyong makes that clear.

Yeah, I gotta reread it; I remember Lady Hyegyong emphasizing her sense of his victimhood, but I guess the stuff about his own self-awareness sticks out less in my memory.

I found the whole letters thing interesting at the time, though: the discovery of those letters kind of got an “Oh, wow, this SHOWS that he knew,” sort of reaction, as far as I remember. People seemed genuinely surprised, like this was confirming something. I kind of thought, “Why is this surpising?” because I’d read the Hyegyong account already.

What I heard when I inquired around was that a fair number of people had been taught a very different version of the events in school–a revisionist history where Sado actually wasn’t that crazy–a little, but not like in Hyegyong’s account–and that he was essentially the victim of a nefarious plot by courtiers and so on. If I remember right, that’s the story that had become prevalent a century after the fact, if I remember right, until Lady Hyegyong’s account started getting attention again.

I suppose the schoolbook authors were trying to avoid the unsettling truth (and gruesome details!), but I’ve been told it was also just sort of felt that it was embarrassing for a Crown Prince to be so utterly bananas.

This makes me really curious to see the old black-and-white biopic that was done in the 1950s, though that tells the reviionist version of the story. (That, and Yi San, the biographical TV series of Sado Seja’s grandson. I have limited patience for those old Joseon Dynasty dramas, but I’d be willing to make an exception–albeit, with a lot of scrolling forward through the boring parts–to see how they handled it in Yi San.)

By its nature I could see the tragedy being one of those stories that gets invested with new or different meanings every century.

Yeah, true, that’s why I’m curious… and also why I was curious about the focus on Sado’s son and his reign in the TV show. (I was like, “Wait, it’s not about Sado? But his story is so interesting…” Of course, if it were about Sado, I think it probably would have too much an anti-Park Chung Hee resonance: abusive/neglectful father figures often seem to sort of link to him in films I’ve see. (Including The Host, whereas Yi San is about recover from a massive family tragedy. I’m tempted to guess it has something to do with some sort post-IMF/post-Park recovery of confidence–after a horribly dark time for his family, Sado’s son becomes an amazing king, or something like that–but I guess I’ll have to sit down and watch it to find out.

If you made a list of Korean narratives I bet you’d find life under a tyrant (further divided into subcategories of foreign, domestic, familial), and recovery from life under the tyrant to be two of the main ones – along with sublimated rage towards one’s parents.

Probably! Familial tyranny also ends up often being allegory for domestic tyranny, just as familial recovery often ends up being allegory for recovery from tyranny, especially when you’re looking at the older generation of postcolonial fictions. Brothers and sisters long separated being united…

When I first got to Korea, I remember being shocked by a newspaper article in one of the English dailies about how younger Korean writers were being slammed by the older writers writing things that weren’t–either directly, or allegorically–about the division of Korea and the necessity for (and dream of) reunification. The younger writers mostly responded with, “But… we want to write about other things that seem more relevant to us today,” but that didn’t really seem to satisfy the older writers at all.

Which, now that I think of it, sort of sounds like the nationalist literary equivalent of the whole unending “SF is dead” wail-and-rant that seems to come up every few years.

Yes, and yes.