BWBC 26: Idol Scholarship

Last week this week’s latest Black Water post, this time by Cynthia Ozick, who if you are anything like me you vaguely remember reading an essay by back in university, or at least being assigned an essay by; whether you read it or not is a matter between you and your conscience.

Depending on a number of variables my chances are 50/50 for having done the assignment, but I’m 100% for having forgotten it all.

Anyhow, here’s the story:

“The Pagan Rabbi” by Cynthia Ozick

Cynthia Ozick’s “The Pagan Rabbi” is on one hand familiar to anyone who’s ever read Machen, Lovecraft, or the like: a narrator meets a person who tells them about another person who was the narrator’s friend, and the second person has a letter from the third person, which they want the first person, the narrator, to read as they hope it explains why everything got as bad as it did, and since this is horror/fantasy the narrator reads the letter hoping to find answers, but instead winds up more alienated from the world.

It’s a style I know and like.

The other part of “The Pagan Rabbi” is heavily steeped in Jewish mysticism and mythology, and that’s where I had to pause and look things up in order to understand the references the characters were making.

The story goes like this…

The Rabbi Isaac Kornfeld has killed himself in an urban park overlooking the bay. His friend, our narrator, goes out to see the tree where Isaac hung himself. He and Isaac grew up together and sought to be Rabbis, but only Isaac succeeded, while the friend opened a used bookstore and became a disappointment to his parents. After seeing the tree the Narrator goes on to pay a visit to Isaac’s wife with the idea of maybe starting to court her. But the widow’s distraught and angry at her husband for not simply killing himself, but for succumbing to idolatry before his death. The narrator’s confused, so the widow presses Isaac’s journal onto the narrator. In the book Isaac records his descent into a pantheistic paganism that saw a free soul in all aspects of the world. In entry after entry, he outlines his proofs explaining the existence of these souls, quoting mythical figures from the Old Testament, and even relaying accounts where he believes he encountered these unbounded souls. He soon looses himself to these visions, spending more time away from home. Finally, in an ecstatic fit, he encounters a dryad in a park near the polluted bay. This leads to his seduction and infidelity as he consorts with the dryad. But he welcomes these transgressions and continues his sport, until the dryad breaks things off, telling him that he has grown too attached to her and thereby his soul has fled his body. When the Rabbi protests, the dryad shows him his own soul wandering the road near the park. The sight of his wandering soul and his abandonment by the dryad sends Isaac tumbling into a despair so deep he hangs himself from the dryad’s tree.

Having read all this the narrator urges the widow to find her husband’s soul where it wanders along the road near the park, but she refuses, and upon seeing how angry the widow is, not at her husband’s suicide but at his idolatry, the narrator forgets about any seduction and goes home to put the whole episode behind him, but not before throwing away all the plants in his house.

Just in case. . .

It’s a good story and the late 1960s Jewish milieu gives the mystic bits familiar touchstones. I mean the story’s plot is literally “young rabbi abandons family to consort with flower child, dooms self”. And the Jewish mystical bits elide seamlessly with ideas from Greek antiquity. The dryad’s a distinct character that might have stepped forth from Ovid or a fairy tale and described in a very tangible way. There’s no doubt that Isaac encountered something numinous and outside the common in that park. And there’s no doubt that the human characters are caught and bound by petty urges and grievances. If you like that mix of the weird piercing the squalidly everyday, The Pagan Rabbi brings a new vantage point to the classic tragic fairy tale of what happens when the mortal seeks to capture the immortal.

Next week, get ready to get wild.

Oscar Wilde!

BWBC 25: More Paint, Different Painting

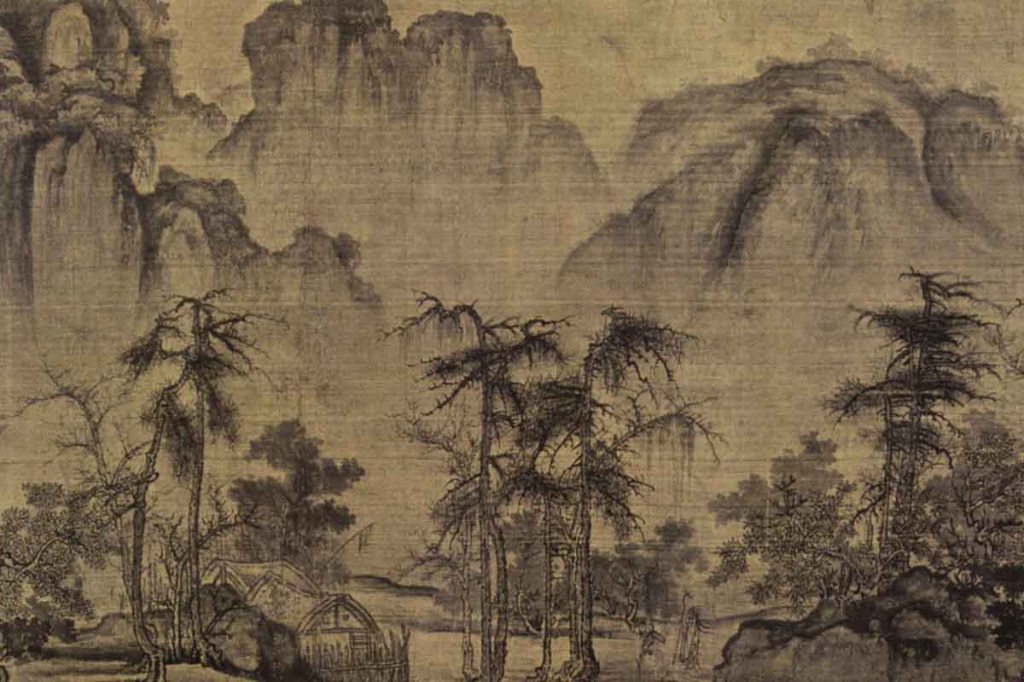

“Autumn Mountain” by Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Ryunosuke Akutagawa lived in the early decades of the 20th century and is considered the father of modern Japanese fiction. To the audience reading this, he might be most notable as the author who wrote the stories that were made into the movie Rashomon. “Autumn Morning” is the story of a painting that may or may not exist. Nothing happens in it except people walk and talk. Now I was once a young man who walked around a lot and spoke a lot of serious nonsense about paintings. Catch me in the right mood or bring up Max Beckmann and you’ll probably get an earful. But I also recognize blather as blather, and art school blather especially when about authenticity, truth, beauty, is a peculiar product all its own.

Anyway, this short story has eight characters in it, and one of them is telling a story to a second one about the painting done by a third which was owned by a fourth one and which a fifth guy who was the first guy’s teacher said was the most amazing painting ever, but after seeing it the first guy’s not so sure the painting he saw is the actual painting, so he tries to buy it, but can’t, then the painting disappears, only to re-emerge years later in the possession of a sixth guy, and this makes the first guy rush out to see it with a seventh guy who’s an art critic and, I think, the fifth guy, and guy one and guy five decide the painting’s not the actual legendary painting, while guys six and seven say it is… and I’m pretty sure I missed a guy in there somewhere, but it doesn’t help that all their names are the Japanese equivalent of Mr. Smith, Mr. White, Mr. Smythe, Mr. Whyte, Mr. Smitt, Mr. Whitt, Mr. Smithwhite, and Mr. Whitesmith. The moral of the whole tale is maybe this legendary painting doesn’t exist and yet by some weird fluke of the imagination what we imagine to be real can be more real than reality.

Manguel seems to have never met a story about a magical scroll painting he didn’t like. It’s a weird thing and I wonder if such stories were the ones that got the broadest reprinting in translation.

“The Sight” by Brian Moore

This one’s interesting because I learned that Brian Moore wrote the novel of a movie I quite like (Black Robe) is based on as well as won a host of awards as well as also being called “my favorite contemporary writer” by Graham Greene, and despite all that I had never heard of Moore before reading this story.

Benedict Chipman is an asshole lawyer in 1970s New York who has recently come home from the hospital after a bit of a medical scare. And while he’s still an asshole, and his doctors have told him their biopsy showed his tumor was benign, the doctors want him to come back at the end of the month for a second test. Chipman’s mostly satisfied, but has some lingering anxiety over this upcoming test, especially as everyone in his life seems to be extremely concerned for him and acting like they know something he doesn’t. This brings him around to discovering that his Irish housemaid claims to have “the sight” and can see when someone’s about to die. She’s let slip to all Chipman’s associates that he doesn’t have long to live, and when Chipman finds out all this the crisis happens.

This is a pretty introspective and psychological story about an unlikable egomaniac’s personality crumbling under a strain of doubt and anxiety. The whole thing probably takes place over the span of 48 hours, and the speculative element is barely present, but it’s a solid diamond of craft and characterization, and I’m glad to have read it.

“Clorinda” by Andres Pieyre de Mandiargues

This one’s a short vignette that reads like Charles Bukowski ghost writing a WB Yeats Celtic fairy tale. A drunkard encounters a miniature fairy knight and promptly subdues them and peels off their armor (like peeling a shrimp) and reveals that the knight is in fact a beautiful tiny woman. Our drunkard proceeds to restrain and disrobe the woman and readies himself to do more, at which point his beastliness gets the better of him and he runs off into the woods to rut and crawl in the dirt. When he recomposes himself once more and returns to where the fairy woman is bound, he finds only the torn string and a drop of blood and has to assume a bird ate her. . . and so that’s why daddy drinks.

This isn’t a story I would seek out and I don’t know if I’d be much excited to read more by the author, but if you like to be miserable or get your kicks watching the squalid mingle with the fantastic you might find this worth tracking down.

Next week… an author you probably read an essay by in university and haven’t read since!

BWBC 24: No Escape

Two stories this week, by the assholes Leon Bloy and Vladimir Nabokov.

Both stories are about the futility of escape, and that no matter how far you travel some places will never let you go and you’ll forever be trapped within their borders. Both stories, while quite enjoyable, have a sketchy quality that suggests better stories than they actually deliver. This isn’t that much of a problem, and the Bloy story in particular made me interested in reading more by him.

“The Captives of Longjumeau” by Leon Bloy

Our narrator who we assume is Bloy recounts reading the news and learning that his friends, the Fourmis, cherished residents in the city of Longjumeau and by all accounts a truly loving couple, have died by suicide.

From very early on some sinister notes start to seep and hint that not everything was quite so wonderful for the Fourmis. First, they live in a house with a garden like “an abandoned cemetery”. Second, they never once left Longjumeau upon arriving there as newlyweds. As the narrator was friendly with the couple, he received a letter from Monsieur Fourmis some days before their deaths in which the Monsieur reveals the truth of their time in Longjumeau and his hopes that he and his wife may at last have found the means to escape it. The truth being that no matter how much they tried to leave the city, even for a daytrip, the world conspired to keep them trapped in the town. Tickets would be misplaced; strange slumbers would strike them while they waited for their trains – one time they even managed to board the train only to have them discover too late that they entered one of the cars to be left in the station. The fact that they can’t escape has led to their isolation and much bad feeling between the Fourmis and their families and acquaintances.

Bloy doesn’t posit any intelligence behind this entrapment nor does he suggest conspiracy among the town’s other inhabitants, but it’s not hard to imagine one at work in the margins: a pact made by the city’s inhabitants to keep the Fourmis in town for some ritualistic reason. Or what if the town requires them in some psychogeographical way? It’s hard not read this story and think of ways to use the same kernel in something myself.

“A Visit to the Museum” by Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov’s story on first read is a bit of a shaggy-dog story, but after a day’s reflection I don’t know whether it’s sinister, an indictment of nostalgia, or still just a shaggy-dog story.

We start with Nabokov talking about this friend of his, a fellow Russian émigré, whose relative’s portrait hangs in a museum. Nabokov doesn’t believe the friend and by his own account thinks the friend’s a bore obsessed with his lost station. But one day the rain forces Nabokov to take refuge in the museum and he goes to seek out the portrait. To his shock it is there, so Nabokov decides right then and there to buy the painting, which the museum’s director doesn’t remember the museum owning, and from there things go south. The director claims some paperwork is required, and Nabokov not wanting to be alone with a group of soccer hooligans who are also in the museum sticks with the director. This then leads him deeper into the museum, which by turns takes on a dreamlike quality of ever shifting vistas and sights, galleries full of locomotives, musical instruments and the like, until finally Nabokov can’t bear it any longer and says they can deal with the paperwork tomorrow, at which point he realizes he’s alone and lost in the depths of the museum. A panicked flight through the dark halls ensues until finally Nabokov throws open a door and walks out into the real world once more. Except it’s not the real world he started the story from, but the world he fled: the Soviet Union. He realizes then that he is likely to be arrested and proceeds to strip naked in order to shed the “integument of exile”. The story then stops with a brief “… and I won’t tell you how I finally managed to get home” paragraph by way of coda, yet the fear remains. Overall, it’s a ride and one that I think is broader than Nabokov’s own hatred of the USSR, but of the way we sometimes remain prisoners places no matter how much we or they might change. That frisson at end hits such a weird note that I have to salute it.

Next week, Ryunosuke Akutagawa.

Who’s he? Stop by next time to find out. Until then, may your path not be your adversary.

BWBC 23: This Time It’s Personal

Two stories for you. One annoyed the hell out of me. We’ll start with the non-annoying one.

“The Friends” by Silvina Ocampo

Two adolescent boys grow up in close proximity to each other because their moms are friends. The boys are dear friends, except one claims to have made a pact with the devil. The other boy is rightfully scared by this, especially after his friend makes several displays of infernal powers. Inevitably the two fall out, and Satan Child attempts to destroy his friend, but in the end manages only to destroy himself.

Ocampo’s a writer I want to like. From a scan of her Wikipedia page I can see she was phenomenally talented, both a visual artist and a writer. I can dig that. But I have yet to read THE STORY by her that will get me hooked on her style. The one I can say I love and that makes me want to rave about to everyone I know. I hope to rectify this at some time by reading her short story collection that the NYRB published some years back and which sits on a shelf in my apartment here gathering dust. But until then all I can say is that her stories are, well, fine.

Now to the story I hated…

“Et in Sempiternum Pereant” by Charles Williams

Oh Charles Williams… how I’ve want to like you. Like with the case of Ocampo you have got this pedigree: a member of the Inklings, occult interests, and books about wizards and ghosts and archetypes from Tarot cards moving about a 1930s London. It’s all so great sounding and makes me eager to read your books, then I do and they’re shit: overwritten, self-satisfied, High Anglican shit. What I feel is the feeling of a potential lover betrayed.

This story is a perfect illustration. It’s in a genre I love: British Man goes for a walk. It has weird metaphysical ruminations sparked by walking on time and duration. And it throws in a wonderful image: a skeletal ghost dressed in rags chewing at their own wrists above a pit that leads to hell. But it’s all written to appeal to a stodgy bunch of Oxford scholars who find any sort of emotional content in fiction must be strangled beneath words, words, more words, and words with extra points for Latin words because fuck those lay people without the proper education.

Anyways, this story is about a retired judge walking to a house to do some scholarship, only to find himself on some weird desolate stretch of road before a cottage that holds passages to both heaven and hell.

I will contend that Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood wrote a lot of sentimental crap, and that Charles Williams never did, but I’d rather either of those hokey writers than Williams any day of the week.

Next time, more assholes.

BWBC 22: Behind the Green Door

Crashing into July like an avalanche. Does anyone else feel utterly exhausted?

This project has reached its halfway point. Although I will likely finish the review series a month or two before years end. I’d rather have that break in November and December than take time off in the summertime only to have to worry about starting up again. Newton’s First Law of Motion tells us a body at rest tends to stay at rest. I feel guilt enough as it is getting the weekly Friday updates out on the Wednesday Thursday Friday of the week after.

But such is life and so it goes.

This week we will be looking at HG Wells’ “The Door in the Wall”.

“The Door in the Wall” by HG Wells

Manguel starts by comparing this HG Wells story to the typical Algernon Blackwood story with Blackwood coming off as the lesser. This got my blood up because I am a big Blackwood fan, and largely unread in the works of HG Wells. Again there’s that ubiquitousness and the feeling like you don’t need to read Wells because he’s been so saturated into the culture. Similar to Bradbury (and others who have appeared in this series to date) and as with Bradbury you realize that your assumptions about the writer were wrong and upon encountering the source, you discover they’re much bigger than you believed. There’s a certain death of aspect in cultural popularity.

“The Door in the Wall” sort of resembles a fairy story, and digs straight into that nostalgia Englishmen have for their boyhoods. It’s also that style of story I love with a narrator telling a friend’s story and trying to square the friend’s monolog with some recent, and likely tragic, event.

Here we have a guy remembering a school friend of great talents who went on to a great career, but seemed plagued by an event that marked him as fae and tragic. This faeness is highlighted by the school friend’s precociousness and talents that were visible from a young age. Later the friend and narrator meet, and the friend unveils something of the tragedy that haunts him.

You see the friend led a stern and lonesome life from the time he was an infant. Then when he was nearly six years old he was out wandering one day when he saw this door. It was a green door in a white wall colored with all the bright reds and greens of autumn. The friend was greatly tempted to open the door and pass within and for some time he debated which course to take. In the end he passes through the door and finds himself in a wondrous world full of everything his lonesome heart desires: wonder, friendship, delights, and games. The garden’s people treat him as a warm friend, and it’s an experience that haunts him even now. For some reason he is sent away by a dark-clad woman who shows him the book of his life and he the child finds himself back out in the street where the loss drives him to have a breakdown. Later when he reveals his vision to his protectors (aunts, nurses, and distant father) they go to great lengths, including violence, to make him forget the event ever happened.

But the green door continues to haunt him and as time goes by, and as the child grows older into adulthood the green door reappears. Always when he’s on the cusp of some achievement, and always he rejects the happiness it offers as he pursues worldly success. Yet, the memories of the garden beyond the door won’t let him go.

He accepts that it is something magical, especially after he finds the door in different parts of town. And he knows, he knows beyond a shadow of a doubt that what the door offers is in every way superior to the material success he has accrued. The world has lost its color. He knows it’s all the laments of a forty-something man, but the door haunts him. Three times in the past year it has appeared and three times he has passed it by. Now though he knows he is ready to pass through and he has taken to wandering the London streets at night, hoping to discover the door again.

And so it’s no surprise when tragedy occurs and the friend finds the door late one night, opens it, and falls to his death in a construction pit. It’s a tragic ending, but the narrator can’t help but feel his friend’s death had some noble aspect in it. A quest linked to the friend’s unconventional talents that drove him onward to success.

All in all an enjoyable story, and the sort that I find crawls under my skin a bit.

It’s also interesting to compare Wells’ story with Algernon Blackwood (and Arthur Machen). Manguel’s right when he makes the comparison to Blackwood, and right too when he suggests Blackwood could be treacly at times. But the Blackwood Machen style posits a world where it’s possible to pass through magical garden doors with some unpredictable regularity, being awestruck and bewildered if we’re lucky; destroyed if we aren’t. For the Blackwood-Machens the risk is not in losing the way, but in embracing the encounter. Which, I guess, is true of the Wells story too after all.

As always I appreciate your continued support and I hope you are doing well in your corners of the world.

BWBC 21: A Bit of Meh

Two stories this week, one okay, one meh.

The okay story is “The Third Bank of the River” by Joao Guimaraes Rosa. The meh story is “Home” by Hilaire Belloc. I didn’t mind reading the former, but the latter annoyed me. If Hilaire Belloc were alive today he’d be one of those tut-tutting conservatives who write op-eds for the New York Times. A David Brooks or Bret Stephens.

“The Third Bank of the River” by Joao Guimaraes Rosa

This story is another in the Something Is Wrong With Dad genre. We’ve seen the type before in Bruno Schultz’s story. It goes like this: for some reason dad’s not right and it’s up to the son to make sense of this while everyone else reacts. In Rosa’s story, dad buys a canoe, renounces the land, and goes to live permanently on the river. The family is thrown into turmoil, and after many harangues to dad, who refuses to relent, the family each make’s some accommodation to their new reality. Years pass. Dad stays on the river. And slowly the family changes with everyone moving away except for our narrating son who stays behind out of loyalty to his father.

In the end the son sets on the idea that he will take his father’s place on the river. But when the time comes the reality of the task proves too great and the son flees his faith in the world shattered because he’s betrayed his father.

I wonder if TVTropes has an entry for Strange Dads? This story also dabbles in that other genre I enjoy: Devotion to the Incomprehensible and/or Futile Task. See my read of the Tartar Steppes.

“Home” by Hillaire Belloc

This isn’t Belloc’s first time in these parts. Awhile back I read The Footpath Way his whole Edwardian paean to English Eco-Fascism.

In “Home” Belloc indulges in the classic “it was all a dream or was it?” bit of corn. The story goes like this: one day while sketching some trees Belloc meets an eccentric man who tells him a story of finding paradise in a French manor house, the “home” of the title. This occurred while on a hiking trip and when the man went to bed in paradise, he woke later on a train and has now been trying to find paradise ever since.

Don’t get me wrong, the story is written well and Belloc can turn a phrase, but he’s a smarmy prick and I find I prefer different smarmy pricks.

Make of that what you will.

Next week, HG Wells!

BWBC 20: Certain Distant Suns

Greetings friends!

This story is great. That’s it. You can go on about your business now. I don’t know if it’s my favorite in the collection*, but it’s certainly a standout.

Joanne Greenberg might be most famous for I Never Promised You a Rose Garden a semi-autobiographical novel about teenage schizophrenia she wrote in the early 1960s under the pen name Hannah Green. I’ve read it. It’s good. I mention it briefly here in this post where I misspell the author’s name. This story is completely different from that novel. It’s also very funny and reads like a Kelly Link story.

“Certain Distant Suns” by Joanne Greenberg

“Certain Distant Suns” is set in 1970s USA among the Jewish American community around New York City. It’s told from the POV of a nineteen year-old girl and the chaos that results when her Aunt Bessie declares that she no longer believes in God. For the first two-thirds of the story nothing fantastical happens. The family first has to deal with Bessie’s apostasy, then with her increasingly more eccentric decisions. She stops believing in Capitalism, germs, and electricity. And with every decision the family panics and wonders how Bessie can possibly survive. But she does, and she becomes an inspiration to the narrator, who notices how much happier Bessie is now that she’s given up all these things.

But this is a fantasy collection, and we’re in a stretch of stories dealing with faith and belief. A cosmic backlash brews against Aunt Bessie. And when it arrives it’s not just a single thing, but two-pronged. I don’t want to give too much away, because you should read this story. I will say that it involves a magic TV among other things.

Greenberg’s style is wry and observant, and it’s fun to see her mix the cosmic scale with the intimately personal. I’m not sure when I’ll again have the chance to read her work, but to stumble at random onto a story like this is exactly what I wanted out of this collection.

* At the end of this project I’ll likely do a Top 20 favorite stories list. And this story will definitely be there.

BWBC 16: Allegorical Realism and Fantasy

And we’re back!

Two stories today: Italo Calvino’s novella “The Argentine Ant” and John Collier’s “Lady on the Grey”. They could not be more different from each other.

“The Argentine Ant” by Italo Calvino

In a lot of ways this story is a straight realist story about a young couple that moves to a new town and have their hopes of finding an easy life there all dashed by the ants that infest the village. As the couple is increasingly tormented they seek help from their neighbors, all of who have pursued different methods to deal with the ant problem. One builds elaborate mechanical traps, another adheres to a complicated routine of poison application, a third lives in complete denial of the ants’ existence even though they torment her. And that’s when you start to think maybe the ants are a metaphor and underneath the realist veneer this story is an allegory for life.

What the ants represent is open to debate. My take is that they embody unfettered nature that contains pleasure and pain, stability and entropy, and which can’t ever be stopped only accommodated. As the story progresses and the ants become more of a nuisance, the situation deteriorates until the couple finally seeks out the man from the Ant Company. He’s supposed to be exterminating the ants on behalf of the government, but no one trusts him and most people in the district believe he’s in league with the ants.

The only relief comes when the family leaves the neighborhood and goes to the beach where the sight of the waves and the sun break the hold the Argentine ants have over them, but there’s no sense that the couple have escaped, only that they’ve discovered a balm for a time.

Give it a read sometime and let me know what you think.

“The Lady on the Grey” by John Collier

Ringwood and Bates are two roguish fail-sons of the penniless aristocrat sort. They’re hangers-on and leeches, living on modest allowances as they travel Ireland in search of game, be it fish, fowl, fox, or human female. Neither are the letter writing sort, and their communications are done via third persons: mutual acquaintances, train agents, barmen, etc. One day while Ringwood’s wondering at his prospects, a message arrives via one-eyed horse dealer that Bates has gone to Knockderry and if anyone saw Ringwood they should tell him that. Ringwood assumes Bates has come upon something good and sets off for Knockderry at once. Of course, when he arrives there’s no sign of Bates and no one in the village knows where he can be found. No matter, thinks Ringwood, he’ll see for himself what the town has to offer (mostly in the way of farm maids he can assault). As he spies a potential victim, he’s interrupted by the arrival of a beautiful woman on a grey horse and the mangy dog that travels behind her. She initiates a seduction and Ringwood can’t believe his luck, despite how annoying her dog is. He doesn’t care that the dog keeps accosting him. So she tells him to come by her lonesome tower house later that night, and Ringwood goes back to the inn to prepare himself. From the innkeeper he learns the woman is the last of an ancient Irish family, and from that Ringwood’s predatory fantasies blossom.

But, of course, things aren’t as they seem.

This is one of those stories you enjoy not because you’re rooting for the characters, but because you like seeing the trap spread around them. When Ringwood finally gets his, you can’t help but feel satisfied.

Do people still talk about John Collier? I feel like he’s one of those writers no one ever talks about but whom provided the seed-story to a dozen well-remembered Twilight Zone episodes. Like Bradbury, he’s the sort of writer you think you know based on one story or book, but whose work as a whole offers a lot more complexity than you realize. Also, there’s the sheer level of craft on display in his stories. The plot might be predictable, but the joy’s in the execution. They’re perfectly designed little narratives.

If you like the Neil Gaiman/Michael Chabon style you might want to check John Collier out.

Next week, a long one from Pushkin!

BW BC 15: In This the Year of Our Lord Entropy

Among the many unsettling things this year of our lord entropy 2020 has revealed, one that snuck up on me is how much all those weird, surrealistic Eastern European writers from the 1930s are starting to make sense. Case in point, Bruno Schulz.

I know I read Schulz back in university and thought him “weird”, but his full eeriness never quite strike me until I read this story of his “Father’s Last Escape” in Black Water. It’s nothing particular or prescient. It’s simply the fact that as weird as things get, the characters all respond to it with an exhausted numbness that I now recognize all too well.

“Father’s Last Escape” by Bruno Schulz

The cleaning girl has no bones and makes a sauce by boiling old letters.

The fur coat in the hall has become alive and attacks everyone that gets too close to it.

And father has drifted away, first into the wallpaper, and then into something crab-like that scuttles and crawls.

Why? Who knows?

The world is in some mutable state and reality can’t be relied upon to behave as one would wish. Father has dreamt too long and deep, and has been transformed. (Although everyone comments on how striking the resemblance is to when father had a human form.)

Schulz is clear in his nods to Kafka, but there’s that banal note to it all that Manguel favors: All the other characters accept the transformation in stride. Sort of. Eventually fate intervenes, but even then it does so in a dreamlike fugue state.

Reality is no longer fixed. Everything is in flux. Father is retreating into a mythic fantasy world and everything seems capable of changing at a moment’s notice. So much so that we’re all numb to it.

Nothing at all familiar in that…

“A Man By the Name of Ziegler” by Herman Hesse

Herman Hesse brings us back to familiar territory, giving us a tale in the classic genre of Guy Gets High, Guy Loses His Mind.

Here our guy is one Ziegler. A typical specimen of his culture and era, well-dressed and confident in his belief that he exists at the pinnacle of culture. He’s smug, he’s proud, he’s self-righteous, and he has a day off so he’s decided to go to the museum and the zoo. But first, we get a full glimpse at how superior he believes himself to be. At the museum he chuckles at how primitive people were in the past, and the way they believed such foolish things. He’s particularly scathing in his views of fortune-telling and the like. But alchemy was all right because it led to chemistry. So while standing before the alchemy exhibit, he pilfers a small pill on display and stuffs it into his pocket. Later at lunch he gives the pill a more thorough examination, and finds its resin scent pleasant. This leads him to tasting the pill, then swallowing it. And then like all novice stoners, he goes to the zoo.

At which point he realizes the drug has allowed him to understand the speech of animals, and they do nothing but mock and insult all the people who stop by their cages. Ziegler’s particularly incensed by the insults from the lions and gets into a shouting match with them. This of course makes the other zoo patrons nervous, and they call the guards, who arrive and take Ziegler away because in true Reefer Madness-style he’s now insane.

So, don’t do drugs!

Or, maybe, if you do drugs, don’t be a smug prick!

Next week… ants!

BW BC 14: Lady Into Fox

David Garnett’s Lady into Fox is a short novella from 1922 about a woman who turns into a fox and the problems this causes for her husband.

In its day Lady Into Fox was highly regarded, winning awards and earning praise from the likes of Virginia Wolfe, Joseph Conrad, and HG Wells. It’s one of those English fantasy stories from the early 20th century, the same era that gave us Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees and Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner. But, despite a reprint in 2004, its legacy hasn’t lasted as well as those other books.

Wikipedia calls Lady into Fox allegorical, but if it is I’m not sure what the allegory is supposed to be. The story’s like one of those old movies that is so fraught with possible interpretations you can easily find contradictory ones. You can read it as feminist. You can read it as misogynist. You can read it as a defense of polyamory and an attack upon it. You can read it as one of those books that could only have been written in a society where uptight, closeted gay men regularly married unconventional, heterosexual women in the hopes of satisfying a society that wanted to pretend neither one existed.

Whatever it is, it’s quite good and worth the afternoon it would take to read it. I’ll put a link to the Gutenberg version down at the bottom. That one has great wood cut illustrations in it by Rachel Marshall, Garnett’s first wife.

A word of warning though: this is one of those stories where a dog dies, and that lets you know that no matter how good things are for the characters at any given moment, a dog has died and therefore everyone’s destined for ruin.

Lady Into Fox

One day, Richard Tebrick is walking with his wife, Sylvia, when suddenly she is transformed into a fox. Why? Who knows. The only explanation given is that her maiden name was “Fox” and maybe that pointed to some “feyness” in her background. Whatever the reason, her transformation causes no end of trouble for poor Mr. Tebrick, because he still loves his wife despite her new form.

And at first, at least after he gets rid of the servants and kills his dogs, everything appears like it will be fine. Sylvia remains human enough in mind to wear dresses, take tea, and play cards. In effect she stays a Lady. But in time her more animal nature asserts itself, and as she grows more fox-like and in line with her new nature, Mr. Tebrick grows more miserable. Yet, despite it all he still loves his wife* and increasingly tolerates her growing more and more wild. Even when she takes completely to living in the forest and mates with another fox, Richard overcomes his jealousy by reasoning no true man can be brought down by a beast, and so his love goes on, untarnished. When the kits are born he calls himself the godfather to her litter and takes to regularly bringing them food and playing with them. Never is the man so happy as when he renounces society and embraces the unconventional. At those times, he doesn’t care at all what form his wife takes, nor how she behaves.

But society can’t abide with those who refuse to fit into it and the bark of the foxhound is never far distant. Tragedy is waiting in the wings and as things roll along it’s only a matter of time before that tragedy comes crashing down. After all, a dog died, and in that act the Tebricks doomed themselves.

Like I said at the start Lady Into Fox is a good little book, even if it’s ultimately a downer. It has that richness to it that makes you want to pick away at it while it draws you in and captivates you.

You can check it out for yourself here.

Even if you don’t download it, you should check that out for the Rachel Marshall illustrations.

And here’s the Wikipedia entry for David Garnett. Why does everything I read about the Bloomsbury Group make me believe they were awful people?

And if you’d like to read another review of Lady Into Fox, I quite liked this one.

Next week, Bruno Schultz!

*I didn’t want to distract from my review, but at one point when Mr. Tebrick goes on a self-loathing drinking binge it’s implied that there’s bestiality. Which… if I go with my take that this is a story about a closeted gay man who can’t handle his wife’s sexuality, then there’s your metaphoric ick-factor.